|

Chapter Seven: Blasted Hopes:

|

|

|

David Hereford has provided us with a photograph of Thomas May's son Samuel and his wife Mary:

|

|

But let us return to the career of Samuel May, the Builder of the May House. Not much is known about Samuel's activities during the 1840s, but we do have evidence that he ran for Congress in 1847. On February 19th, 1847, this notice appeared in the Louisville Daily Journal:

Samuel May announces himself through the Frankfort papers as a candidate for Congress in the 6th Congressional District of this State.

During the 1840s, the Louisville Daily Journal was the mouthpiece of Kentucky's Whig Party. Its feisty editor, George Prentice, liked to satirize the faults and foibles of Democratic Party politicians, whom he called Locofocos. On March 6th, 1847, shortly after Samuel's announcement that he was running for Congress, Prentice published this letter satirizing Samuel May:

Louisa, Ky., Feb.25, 1847

GENTLEMEN: Perhaps you have already noticed the announcement in The Yeoman of another old veteran stump-orator to represent the Sixth Congressional District of this State in the next Congress. This old veteran is none other than old Samuel May. What kind of a selection do you suppose!!! The old man is no doubt honest in his domestic affairs, but there is one objection to him. There is not one single letter of the 26 that he can identify. The old man thinks he is the choice of the Democrats, and I understand he is brought out by a considerable force of the Regulars, and a portion of the Dragoons--all belonging to that party whose creed is, the President can do no wrong.

Although the mud-slinging character of this letter tends to cast doubt on the veracity of its statements, it nevertheless raises an interesting question.

Was Samuel May literate? I would prefer to think so, but documentary evidence proves that he wasn't. Last summer I spent several days going through the Henry Scalf Collection at the Allara Library at Pikeville College. The collection contains court records that were formerly stored in the offices of the Floyd County Court. Most of these records were damaged during the 1957 Flood, and if Henry Scalf hadn't saved them at the last moment, they would have been thrown away. Devon Scalf, Henry's son, tells me that on the day after the flood, Henry drove a pick-up truck to the courthouse and retrieved the documents. Then he took them to his home on Mare Creek, spread them out on the ground, and let them dry in the sun.

One of the documents which I found in the collection is the bond which Samuel May gave to the Floyd County Court during the period when he was building the Floyd County Courthouse. It is dated November, 1816 and labeled "Bond for Building Jail & Courthouse." At the bottom of the document are the signatures of Alexander Lackey, Henry Stratton, James Young, Daniel May, and "Saml May X his mark."

The letter from the Louisa man shows that by the 1840s, the frontier period in Eastern Kentucky was coming to an end. By that time, the rough manners of the frontiersman were beginning to fall into disrepute, and voters were looking for other qualities in their elected officials beyond the energy and determination that had served them so well during the early period. By the way, those readers who, like me, have an interest in protecting Samuel's reputation can find consolation in the fact that even his political enemies were willing to admit that he was "honest in his domestic affairs."

During the 1842-47 period, Samuel continued to accept work as a contractor, and in 1848, according to Henry Scalf, he entered into a short-lived partnership with John Howe and William Foster for the purpose of mining coal. Scalf calls attention to the fact that the contract mentions "coal banks opened by the said party of the first part." In other words, Samuel had been out in the county prospecting for a rich coal seam.

On August 29th, 1849, according to Scalf, Samuel entered into a partnership with Thomas Griffith of Cincinnati. The purpose of the partnership was "to carry on lumbering and coaling business." The two men would be "equal partners in sawing lumber, building boats, and digging coal . . . Said May has steam saw and grist mill nearly completed."

The contract sets out the firm's intentions in detail:

May and Griffy [Griffith] are to saw plank, grind on their grist mill, build boats for plank and coal, buy saw logs, boat gunnells, dig coal, and run the result of their labor to market or sell where they or either of them think best.

This second partnership was also short-lived. Sometime in the Fall of 1849, word reached Prestonsburg that gold had been discovered in California. Samuel reacted to this news in a way that must have surprised his friends. He terminated his agreement with Griffith, wound up his other affairs, packed his bags, bade his wife and children goodbye, and headed for the western gold fields. Since digging for gold is hard work and he was beginning to feel his age, he took along his twenty-year-old son Andrew and another young man by the name of White. At age sixty-six, Samuel had decided to risk everything on one last roll of the dice.

I must admit that I began this project with only the foggiest notion of who Samuel May was or what he represented. In her Ballad For a Forty-Niner, Gertrude May Lutz asks the following question:

All manner of men came to Hantown's Hill;

But why would a man like Samuel May

Leave his mansion one sunlit day--

Leave Kentucky for Placerville?

The question is a good one. Putting aside the historical inaccuracy of "Leave his mansion," why did Samuel so suddenly decide to give up everything he had worked for here in Floyd County? On the surface, at least, his decision seems uncharacteristic of a man who had devoted so much of his life to public service. Why did a solid citizen like Samuel May catch the gold-rush fever?

Some will say that the answer is simple--he needed to recoup the losses which he had suffered during the Depression of 1837-43. That's true as far as it goes, but there may have been other motives as well. By 1849 Samuel had good reason to be disillusioned with a banking system that favored metropolitan banks over rural ones, especially by its practice of hoarding gold in metropolitan vaults during times of economic crisis. Samuel had seen this happen twice in his lifetime, and the second crisis had cost him his farm and ferry.

Samuel knew that if Floyd County was ever going to become truly prosperous, it had to acquire large amounts of a commodity that retained its value through good times and bad. I suspect that Samuel went to the gold fields not just for himself and his immediate family, but for all the people in his community. He was hoping to strike it rich and give Floyd County its first independent bank.

Although it appears so at first glance, the boldness of his decision wasn't uncharacteristic of the man. Samuel had played long shots from the very beginning. The choice he had made in his youth to tie his destiny to a remote mountain hamlet had been daring for a man of his ability, and so had his later decision to run for the state legislature. Moreover, though I can't prove it, I suspect that he mortgaged his farm in order to pay for his political campaigns. His decision to accept the contract to build the courthouse had certainly been bold, considering the constraints which he had to work under. However, for sheer, downright audacity, what can surpass his decision to build an elegant, two-story brick mansion in the middle of nowhere?

When Samuel and his companions traveled to California, the first leg of their trip was probably by steamboat. Carol Crowe-Carraco says that Captain Daniel Vaughn's Tom Scott began regular service to Louisa in 1852. Embarking at that town or Catlettsburg, they probably traveled down the Ohio to Cairo, and then up the Mississippi to St. Louis. From there they probably steamed up the Missouri to Independence, the stepping-off point for the California Trail.

From Independence they would have traveled overland up the Blue River into Nebraska, followed the Platte River up into Wyoming, stopped at Fort Laramie, signed their names on Independence Rock, crossed the Green River, went down Wasatch Canyon into the Mormon Settlement around Salt Lake, crossed the Great Salt Lake Desert, mounted the high passes of the Sierra Mountains, and descended into the Sacramento Valley. On the overland leg of their journey, they probably traveled by saddle horse, carrying only the essentials--food, bedrolls, changes of linen. Their money they carried in money belts strapped around their waists. You can be sure, too, that they carried Colt revolvers or other weapons.

Alfred

Jacob Miller's painting of Fort Laramie, 1851 shows us

what the Wyoming High Plains looked like when Samuel and his

two companions traveled west in 1849:

Alfred

Jacob Miller's painting of Fort Laramie, 1851 shows us

what the Wyoming High Plains looked like when Samuel and his

two companions traveled west in 1849:

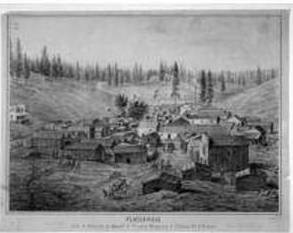

Relying on the family traditions of Colonel May, Andrew Jackson May's son, whom she knew personally, Josephine Fields has told the story of Samuel's final years. According to her, he and his boys built a cabin near Placerville, a boom-town on the south fork of the American River. "In and around the diggings of Placerville," she says, "they sought their fortune. They found some of the metal that had lured thousands from the East, but no vast fortunes accrued to any of the trio."

Here is a rare print of Placerville which I found in the huge image database of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

For Samuel the hard work and constant exposure soon took their toll. In January 1851, he developed a fever, went to his cabin, and "lay down to die." With his son Andrew and the other boy at his side and the cold wind whistling through the chinks, he lingered for several weeks in a state of delirium. At one point, according to Miss Fields, he called his son to his bedside and made an unusual request:

Most of all he wanted coffee. He could smell the aroma of it. He would tell his son, and so Andrew Jackson May rode for miles around the diggings, asking for coffee. But this item was a luxury most prospectors had foregone months ago. However, Andrew's persistent search brought him to a camp larger than the others. Upon asking if there was any of the desired berries, he was told that there was, but that none were for sale.

Tradition has preserved the dialogue between the digger and young May down to this day. "But I must have coffee," Andrew said. "You'll get no coffee here. Coffee is scarce," the digger replied. "But my father is dying, and, most of all, he wants coffee. I do not want it for myself." The digger's countenance changed. "Why didn't you say so in the first place?" he asked. Andrew got the coffee for his dying father.

Samuel breathed his last breath on February 27th, 1851. His life ended with a deathbed scene worthy of Dickens. Momentarily revived by the hot coffee, he roused himself and gave the boys directions regarding his burial, the disposition of their gold, and their return trip to Kentucky. Then, with a great effort, he placed his hands upon their heads and pronounced a benediction. "God bless you both," he whispered. Then he died.

In 1898, during the period when he was practicing law in Tazewell, Virginia, Andrew Jackson May traveled to California, walked the hills around Placerville, and tried to locate his father's grave. By then, however, the place had changed so much that he couldn't find it. "As for man," says the Psalmist, "his days are as grass: as a flower of the field, so he flourisheth." Since no stone marks Samuel's grave, his real monument is his house. It's up to us to preserve it.

![]()

CLICK HERE to see a facsimile copy of the last known official record of Samuel May which is recorded in the 1850 U.S. Census for California.

The rare print of 19th Century Placerville comes to us courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Alfred Jacob Miller's beautiful painting of Fort Laramie, 1851 comes to us courtesy of Jim's Fine Art Collection, one of the best art galleries on the web.

© 1997 Robert L. Perry