Chapter Three: Building the May House

In 1816 Samuel May began building the house which is the subject of this book. According to Tress May Francis, the brick used in its construction was manufactured at the site, or, as she puts it, "burned on the farm." The lime for the cement was made by pulverizing mussel shells collected from the Levisa Fork of the Big Sandy, which in those days was home to numerous species of fresh-water clams. According to Josephine Fields, the lumber for the house was whip-sawed from logs hauled to the site, and then cured and hand-planed to meet the builder's specifications. Indeed, the construction of the house must have been a laborious and time-consuming process.

Josephine Fields, who published an article about the house in 1952, noted that "The remains of the kilns can be discovered even today, after a lapse of 135 years." She continues:

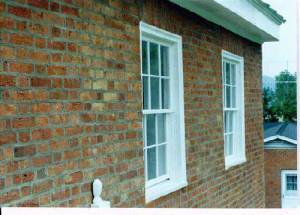

The design of the house provides much evidence of Samuel May's skill as a builder and architect. Tress May Francis, writing in 1956, pointed out that the bricks in the front wall of the house are laid in a Flemish bond, an extremely strong pattern of construction. By the way, Indian fighter William Whitley used this pattern when he constructed the walls of Sportsman's Hill in 1788. All the walls of the house, including the interior partitions, are four bricks thick, necessitating unusually deep window sills and door frames. In other words, there are structural reasons why the house has survived as long as it has. Francis continues:

Tress Francis isn't the only writer to praise the craftsmanship of the house. Gordon Moore, writing in 1961, marveled at its hand-carved mantels and spacious rooms. The wide, western-style porch presented him with a problem, however, because its size and placement weren't in keeping with the Federal style. Moore reached the conclusion that the wide porch wasn't original, and subsequent scholars have seconded this judgement. When the house was restored in 1997, a new front porch was added to the house that was smaller and more typical of the Federal style. Here is a photo of the house taken in the early 1980s, showing the large plain porch:

One of the riddles still to be solved is the purpose of the second-story door, which before the restoration opened onto the roof of the front porch. In the early days it probably provided access to a balcony protected by hand-rails. Given Samuel May's political proclivities, one can easily imagine what purpose such a balcony would have served during Democratic Party rallies and Fourth of July celebrations. In 19th Century American towns, saloons and hotels often had balconies, as we all know from watching too many Hollywood westerns. At any rate, in the days before public address systems, balconies were handy things when politicians were called upon to address crowds. At any rate, because of the existence of the second-story door, Architect Joseph Argabrite decided to add a balcony to the new, Federal-style porch that was added to the house during the restoration. Although the May House has only six rooms, they are large ones, and several of them measure eighteen by twenty feet. The more I study the house, the more I see that it was designed to be not just a private home, but a community hall. Its porch and balcony were intended to add pomp and dignity to political occasions. Its large rooms were fashioned not just to accomodate weddings, funerals, prayer meetings, cornhuskings, and the like, but to provide shelter during storms and Indian attacks. Here is a recent shot of Samuel May's Parlor, the largest room in the house:

In 1816, although the immediate danger had passed, memories of Indian atrocities were still fresh in the minds of most Big Sandians. Less than three decades had elapsed since a mixed band of Cherokees, Shawnees, Delawares and Wyandottes had raided Jenny Wiley's cabin on Walker's Creek in Abb's Valley--in Tazewell County, Virginia--and murdered four of her children. Furthermore, tribes had hunted on the Big Sandy as late as 1793. Samuel May was keenly aware of the needs of his community, and the design of his house relects this fact. It is very likely that the windows of the house originally had shutters. J. Winston Coleman's Historic Kentucky, a collection of photographs of early Kentucky homes, demonstrates that shutters were typical of the Federal style. Wickland, Wakefield, Locust Grove, and Desha Glen all have shutters, and so does the O. P. Ely House in Knox County, a Federal home of the same size and outward design as the May House. Another argument for the case is the fact that the courthouse which Samuel built during the 1818-1821 period was protected by "green Venetian shutters." Furthermore, since glass was a precious commodity on the American frontier, Samuel would have wanted to protect his windows from hail and strong winds. What outbuildings did the May Farm have? If it was like other Kentucky farms of the antebellum period, it included a free-standing kitchen connected to the house by a walkway, a barn, a smokehouse, a stable, a carriage house, a corn crib, a well, a privy, and the slave quarters. E. B. May, Jr.--known to his friends as Junior May--who spent part of his childhood on the farm, recalls that his father's smokehouse was located immediately south of the back portion of the house, and that a one-story barn was situated on the land now occupied by his present home. The barn contained a fattening pen for hogs and was adjoined by a hog lot. An orchard was located on the land now occupied by Pizza Hut and Wendy's Restaurant. This photo, taken by Tress May Francis in 1936, shows the May House smokehouse:

What kind of crops did Samuel raise? 19th Century Kentucky historian Lewis Collins, whose Historical Sketches of Kentucky (1847) includes descriptions of individual counties, says this about Floyd County agriculture during the 1840s:

My main sources for information about the May Farm are Bill and Junior May, the sons of Elijah Brown May and the former owners of the May House. According to Junior May, the farm annually produced 250 bushels of corn during the period when it was owned by his father. During their boyhood years Bill and Junior often listened to the stories of Johnny Powers May, their grandfather, the son of William James May and Cynthia Powers May. Johnny passed along the tradition that Cynthia Powers May had owned a spinning wheel. During Elijah's boyhood, the wheel was stored in the May House attic along with other family heirlooms. When the house was rented to tenants during the period from 1912 to 1933, they chopped these relics up and used them for firewood.

© 1997 Robert L. Perry |

The front doorway

of the house is distinctive. Instead of the standard fantail

transom of most Federal doorways, it is accentuated by oblong

rectangular sidelights. Incidentally, this kind of sidelight

can also be found on the O. P. Ely House in Knox County,

Kentucky, a Federal home of the same size and exterior design

as the May House. The door of the May House is

four feet wide and has six hand-carved panels. The original brass

lock is still in place, and it still works. Reproductions of

this kind of lock may be obtained from the Colonial Williamsburg

Foundation at a cost of $725. Keys are sold separately and cost

$46.

The front doorway

of the house is distinctive. Instead of the standard fantail

transom of most Federal doorways, it is accentuated by oblong

rectangular sidelights. Incidentally, this kind of sidelight

can also be found on the O. P. Ely House in Knox County,

Kentucky, a Federal home of the same size and exterior design

as the May House. The door of the May House is

four feet wide and has six hand-carved panels. The original brass

lock is still in place, and it still works. Reproductions of

this kind of lock may be obtained from the Colonial Williamsburg

Foundation at a cost of $725. Keys are sold separately and cost

$46.