|

|

|

|

|

Robert Perry, who was an English Professor, came to Prestonsburg Community College in 1989 and soon proved that he had what he termed, "well-developed nesting skills." There is no doubt that his leadership was key to the restoration of the historic Samuel May House. His death in 2003 was mourned by many friends in Eastern Kentucky.

The

Rest of the Story

about

the Historical Marker

Robert Perry: 1998

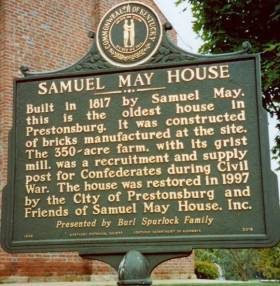

As the major restoration work was coming to fruition, Dr. Perry undertook the task of getting the State of Kentucky to authorize the placement of a historical highway marker at the Samuel May House. After going through a typical year-long bureaucratic maze he finally got "approved wording" for the marker from the staff of the Kentucky Highway Marker Program, a branch of the Kentucky Historical Society in Frankfort.

In an article he wrote for the December 1998 edition of The Floyd Countain quarterly, he cited some disturbing modifications to the version he had proposed for the marker. I have chosen two complaints that stand out from the others.

First Complaint

On the side of the

marker headed SAMUEL MAY HOUSE, Robert had described the house as:

"the

oldest brick house on Big Sandy."

No historians have

ever been known to dispute this claim. The staff experts, however,

were being overly cautious when they chose to edit the phrase to:

"the

oldest house in Prestonsburg."

Robert, with his newly found attachment to the history of the region, was not pleased! He called it "cultural paternalism." Asking, "Who has given them permission to rewrite the history of Eastern Kentucky?" Through his research over the past five years he had, "reached the conclusion that the May House was indeed the oldest [brick] house in the Big Sandy Valley."

Dr. Perry explains:

" First of all, we have indisputable proof, in the form of deeds and entries in ledgers, that the house was built in 1817."

"Second, we know that in 1817, Prestonsburg was the only platted town in the entire valley."

He emphasizes that the other towns on the Big Sandy were founded after 1817: Louisa was surveyed in 1822, Pikeville was surveyed in 1824, Paintsville was founded in 1834, and Catlettsburg was platted in 1849!

He asks of the experts at the Kentucky HIghway Marker office, "are they aware of the fact that in 1817, Prestonsburg was the only town in the entire valley?"

Prestonsburg was the seat of justice for Floyd County, which encompassed most of the upper region of the entire valley. Its original boundaries of more than 3,600 square miles were formed from Mason, Fleming and Montgomery Coutnies in 1800. During the next 84 years, fifteen additional counties were entirely or partially carved from this large territory, leaving about 400 square mile in present-day Floyd County.

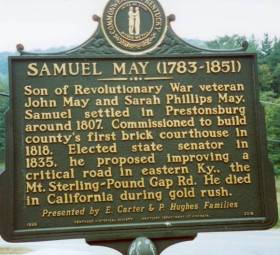

Second Complaint

On the side of the

marker headed SAMUEL MAY (1783-1851) Robert proposed the wording of a

sentence as:

"Elected

to State

Senate in 1835, he led the fight to build the Mount Sterling-Pound

Gap Road, the first state road through Eastern

Kentucky."

The staff edited it

to say:

"Elected

state senator in 1835, he proposed improving a critical road in eastern

Ky.,

the Mt. Sterling-Pound Gap Rd."

It was the alteration of Eastern Kentucky to eastern Ky. that most angered Dr. Perry. He calls it "cultural paternalism" and asks:

"What on eatrh

is wrong with capitalizing the "E" in "Eastern Kentucky?"

"What possible

objection could anyone have to this particular usage?"

"Any English

teacher can tell you that names of geograph ical regions are

customarily capitalized. In my home state, for example, regions of

the state are regularly referred to as "Eastern- Nebraska"

or South-Central Nebraska."

He finally comes to the conclusion:

"Evidently Frankfort's cultural czars are afraid that we Eastern Kentuckians are getting too big for our britches. Therefore they may have seized the opportunity offered to them by this litle roadside marder and are trying to teach us a lesson in humility. They are evidently trying to tell us that we are lower-case Kentuckians, not higher-case ones. I hate to say it, Frankfort, but everything people say about you is true."

Robert, as a Professor of English, took this opportunity to encourage everyone in Eastern Kentucky to make it their regular habit to capitalize the "E" in Eastern Kentucky. . . And as for the Frankfort bureaucrats he says, "if this be treason, make the most of it!"

Source:

How

I Learned About Frankfort's Cultural Paternalism

by Robert Perry

December

1998 edition of The

Floyd Countian,

Published

by the Floyd

County Historical & Genealogical Society

in Prestonsburg, KY

Robert may have also published his

objections to this "rewrite of the history of Eastern Kentucky"

in the Floyd County Times.

More

Facts to Consider

Fred

T. May

2005

The Oldest Brick House on the Big Sandy

I take the liberty

to add another set of facts to support Robert's claim that Samuel May built

"the

oldest

brick house on Big Sandy." Prior to 1817, and for many years

afterward, homes in the valley were log structures, built from the

plentiful hardwood forests that covered this entire region. The first

home in the valley that wasn't constructed of logs was built by John

Graham a few miles south of Prestonsburg in 1807. Henry P. Scalf

tells us that lumber for the twelve-room house was sawed on the

grounds and the first windows in the valley were brought in on

horseback. Graham family records say it took five years to complete

the building.

**

"The Graham Castle" completed

in 1807 **

By

1898 it had fallen into such disrepair that it was razed.

Photo

from The Big Sandy Valley by W. R. Jillson in 1923

During the early decades of the 19th Cecntury, this region was very sparcely populated and had no transportation or manufacturing businesses. Rugged trails over the mountain from Virginia were the primary routes into the valley for many years. Historian Henry P. Scalf in Kentucky's Last Frontier, tells us that for transportaion on the Big Sandy, which flows north to the Ohio River, the settlers "made birchen canoes or dug-outs of poplar and floated on its bosom." Scalf adds, "At first the articles of merchandise that moved at all upon the stream were furs, chiefly bearskins, demanded by Napoleon's army for use in making his grenadiers hats." This business abruptly ended at Waterloo in 1815.

The next form of transportation - which carried produce out of the region and returned upriver with needed supplies- used push-boats. "They foated easily downstream, but the return trip required long push poles." Salt was the primary imported commodity. Enoch Auxier is credited as the enterprising man who first used these larger boats for his salt transportation business. Steamboats first traveled upriver to the forks of the Big Sandy at Louisa in Lawrence County in 1837 and within a few years their route extended beyond Pikeville in Pike County.

I use these facts

introduce the obvious question: Where would anyone get bricks to

build a large two-story home in the wilderness of Eastern Kentucky in

1817? Obviously they weren't transported over the mountain passes or

carried upriver on dug-outs or push-boats. The answer is simple, they

were fired on the grounds of the building. May family genealogist

Tress May Francis describes the process if her history of the May family:

May Genealogy:

Southern Branch with Biographical Sketches: 1776-1956.

Samuel May built a brick house on this land in 1817. The red brick was burned on the farm; the clay being dug from a part of the farm a short distance from where the house was built. The writer remembers seeing the red coloring in the clay knoll adjoining what were later a large apple orchard and this knoll must have been where they had the kiln. Lime from the mortar was made by burning or pulverizing mussel shells. The brick is laid in a Flemish Bond along the front of the house, but in a more random fashion along the sides and back. The exterior walls are four bricks thick, which accounts for the deep windowsills and doorframes throughout the house. The interior walls and partitions are also four bricks thick and extend from the ground to the roof. The architecture of the house is Colonial in design. The steps leading to the front entrance are of a sanded native stone, and are three or four feet long, and still in use today. The same kind of steps is used at all of the doors around the house. Over the front door is a transom of three oblong panes of clear glass, also on each side of the door are oblong panes of glass that extend half-way down the side of the door, or on a line with the window sills. The door itself is four feet wide with six panels - the original key and lock are still in use, and they are both rather a large affair, and the key rather heavy.

**

Photo of the Samuel May House about 1985 **

At

this time it had stood for about 168 years.

more

photos 1936

& 1996 | Restoration

About 1807 Samuel worked as a carpenter with Thomas Evans, a contractor who was soon to become his brother-in-law, to build a log courthouse in Prestonsburg. Early in 1808 it was completed, but within a month or so it burned and soon afterward Evans was commissioned to build another courthouse, but within a few years it proved to be inadequate in size. But how could Samuel May afford to go to such extreme expense to build a brick home in 1817? He probably had some money from the estates of his father and father-in-law who had died a few years earlier, but expensive homes weren't considered as wise investments at the time. Was there another motive?

It probably was no secret around town that the Court Justices had begun talking about building a larger courthouse. Floyd County Court records show that on November 17, 1818 commissioners were appointed "to draft a plan for a new brick courthouse and to fix the place on the public square whereon it shall be erected." The design for the brick, two-story building is spelled out in detail in Floyd County Court Book 3. Scalf tells us that the project was advertised for bidders in Floyd, Montgomery and Fleming counties.

In the meantime, Samuel May had the foresight in 1817 to build the first brick kiln in the region on his newly acquired property north of town. He first used it to fire bricks for a large two-story home and more significantly gained an advantage in the bidding for the courthouse contract, which was granted to him. The new courthouse was accepted by the Court in September 1821 and served the county for seventy years.

To learn more about Samuel May, read his biographical sketch

Sources:

|

Francis, Tress May |

May

Genealogy: Southern Branch with Biographical Sketches: 1776-1956. |

|

Perry, Robert |

The

Oldest House in the Valley, Friends of the Samuel May House, Inc., |

|

Scalf, Henry P. |

Kentucky's Last Frontier, Pikeville College Press, Pikeville, KY, 1972 |

|

Wells, Charles C. |

Annals

of Floyd County, Kentucky: 1800-1826. Gateway Press, Inc., |

|

Jillson, Willard Rouse |

The Big Sandy Valley, John P. Morton & Co., Louisville, KY, 1923. |