|

The Great Migration

The War of the Grand Alliance, fought against the invader King Louis

XIV of France at the end of the Seventeenth Century, punctuated the

despair of the people in the Rheinland Palatinate as their villages

and cities were laid to waste. Following the end of the war, the

people were slow to rebuild and were easily tempted by many

opportunities promised in foreign lands. The winter of 1708-09 was

unusually cold in the region, freezing and destroying many trees and

vines. Queen Anne of England solicited as many as 13,000 Palatines ("Pfälzer")

to come to London where they would be dispersed to Ireland, North

Carolina and the Hudson River Valley in America.

The Meÿs leave for America Johann Adolf Meÿ was the first member of the family to leave the village of his birth. In the spring of 1747, soon after his thirty-sixth birthday, Adolf gathered his mother, brothers and sisters around him to bid them good-bye. It probably was the last time they were ever together. We don't know if Adolf left with a wife or children, but we do know that he applied for his manumission along with three other people from Niederhausen, and arrived in Philadelphia aboard the ship Two Brothers on October 13, 1747. There is no other record of Adolf. After Adolf left home, twenty-eight year-old Johann Leonhardt probably took the lead in planning for the family to leave for America. He was three years older than Johann Daniel and five years older than Frantz Peter, the youngest son. About 1743, Leonhardt had married Maria Barbara Lorentz, but by 1747 his wife and their two infant children had died. Prior to 1748, the only sons of Johann Nickel and Maria Catharina Meÿ known to have been married were Johann Nickel (Jr.) and Leonhardt.

Members of the Lorentz family, close friends and neighbors of the

Meÿs in Niederhausen, were making similar preparations. It

appears that the Meÿ and Lorentz families were eager to leave in

the spring of 1748, so they could be on board the first ship out of

Rotterdam that summer.

Travel on the Rhine was the only practical way to get to Rotterdam on the North Sea. There was no established road system for transporting heavy loads through the various principalities dotting the countryside along the way to the large Dutch seaports. River travel, however, wasn't inexpensive. As many as forty toll-stations were located along the Rhine where fees were extracted from travelers and captains before their barges were allowed to pass certain stretches of the river. Many delays along the way intentionally forced travelers to stay overnight and shell out their money. The Meÿs probably left Niederhausen about mid-May, joining many other immigrants as they floated down the Rhine, probably arrived in Rotterdam by the middle of June, 1748. Upon arriving in Rotterdam, they confirmed the schedules of the first ships bound for America. The times of ship arrivals and departures varied from year to year. The ship Captains sought to get the best cargo for their journeys, and humans weren't the preferred cargo on the best ships. They attempted to select their cargo to maximize profits for themselves and the ship owners. Since their ships were not normally outfitted for carrying passengers, special modifications had to be made for the immigrants. After passage was booked on the Edinburgh, captained by James Russel, the weary immigrants could only wait, wonder and pray about the uncertainties that lay ahead. Securing the best accommodations they could afford, probably sharing space with the Lorentz family, the Meÿs made themselves as comfortable as possible as they awaited the arrival of their ship. The Meÿ brothers and sisters must have been apprehensive about the affect the rigorous journey thus far had on their sixty-two year-old mother, Maria Catharina, and on any children that may have been sailing with the group to America.

Crossing the Atlantic In 1748, a total of only seven immigrant ships sailed from Rotterdam to Philadelphia. However, soon afterward the number of immigrants seeking passage would grow, with the following six years being the busiest of the century. More shipmasters were finding it profitable to fill their holds and decks with human cargo. The Meÿ and Lorentz party was on board the first ship to leave Rotterdam that year. They knew very little about the large, untamed land they soon would enter. In stark contrast to the region they had known as home in Germany, their new home would be in the middle of a sparsely populated wilderness. Allowing about ten weeks for the voyage to America, we can estimate the date that the Edinburgh left its mooring in Rotterdam with the Meÿs aboard to be about the first of July, 1748. After clearing the channels of the Rhine delta, Master James Russel maneuvered his crowded sailing vessel across the choppy tides of the English Channel from Holland to Portsmouth, England. This route took the immigrants through the Straits of Dover where they saw the famed white cliffs in England and the quite sandy shore of Calais in France. In Portsmouth, a large seaport in southern England, the British authorities checked the ship's manifest and gave official approval for Russel to continue on to the Colonies. Authorization to approach Portsmouth on the waters between the Isle of Wight and the mainland was often delayed for larger ships owned by the Crown, and for more important ship companies. Often the immigrant ships were sent to the smaller port of Cowes on the island. The time for the channel crossing and the approval process in England could, much to the dismay of the passengers, take as long as two weeks. After leaving Portsmouth about mid-July, the treacherous and unpredictable Atlantic lay before them. These were the warmest months for crossing the ocean, and despite the risks it was the best season to transport immigrants. However, as we are reminded every year, this also is the season for hurricanes moving westward from the lower latitudes and ravaging the Atlantic shore of North America. Fortunately, despite the weather, most ships sailed from England to Pennsylvania in less than eight weeks. The passengers were typically in very bad physical condition upon arrival. The captains had no resources to meet the needs of such a large number of people, and they gave little sympathy to complaining immigrants. Those traveling in family groups were capable of caring for each other, so they had the best chance to survive the journey.

Arriving in Philadelphia For an unexplained reason, the ship's passenger list does not include the name of Johann Daniel Meÿ. We can only speculate why Daniel's name is not recorded. Perhaps he simply was too ill to sign with the others and was allowed to leave the ship later. Reference are made to immigrants on some ships who were "Sworn sick on board whose names are not in the List." Regardless of the circumstances in Philadelphia, we have numerous other records of Daniel, up to the time of his death about thirty years after he arrived in America. As a leader in the religious, social and business community of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Daniel plays an important role in the establishment of the Meÿ family in America.

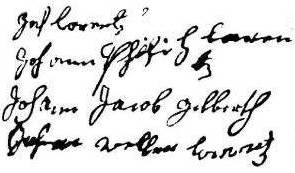

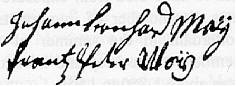

This transcribed list, along with facsimile

copies of the original signatures,

Another transcribed list from a second set of Oaths was published

Recent research by genealogists of the Lorentz (Lawrence) family has questioned whether all of the Lorentz passengers were from the Lorentz family of Niederhausen. Some genealogists have confirmed that they are descended from Johann Philip Lorentz of Niederhausen. Others of the family who are known to have immigrated from Niederhausen with Johann Phiilip were Johan Jakob Lorentz and Anna Maria Lorentz. It is reasonable to assume that Johan Jakob Lorentz was the Hans/Johan Lorentz on the list. However, a genealogist of the Lorentz family who has extensively researched Lorentz family records from Niederhausen has concluded that Hans/Johan Lorentz on the Edinburgh was not related to the Lorentz family members known to have been on the ship. He also found no record of a Johann Velten Lorentz from the village. It is known that this genealogist's ancestor, Johannes Lorentz, later married the daughter and sister of two men on the ship, Valentin Huth and Valentin Huth, Jr. Y Chromosome DNA tests have shown that he doesn't have common male ancestors with descendants of Johann Philip Lorentz. It is his working conclusion that Johannes was the Hans/Johan Lorentz on the passenger list.

Johann Leonhard and Frantz Peter appear to have preferred to spell the family name as Maÿ, instead of the older form of Meÿ. Most of the Court records in America use the Anglicized spelling, May, which I also use in subsequent essays.

REFERENCES:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||